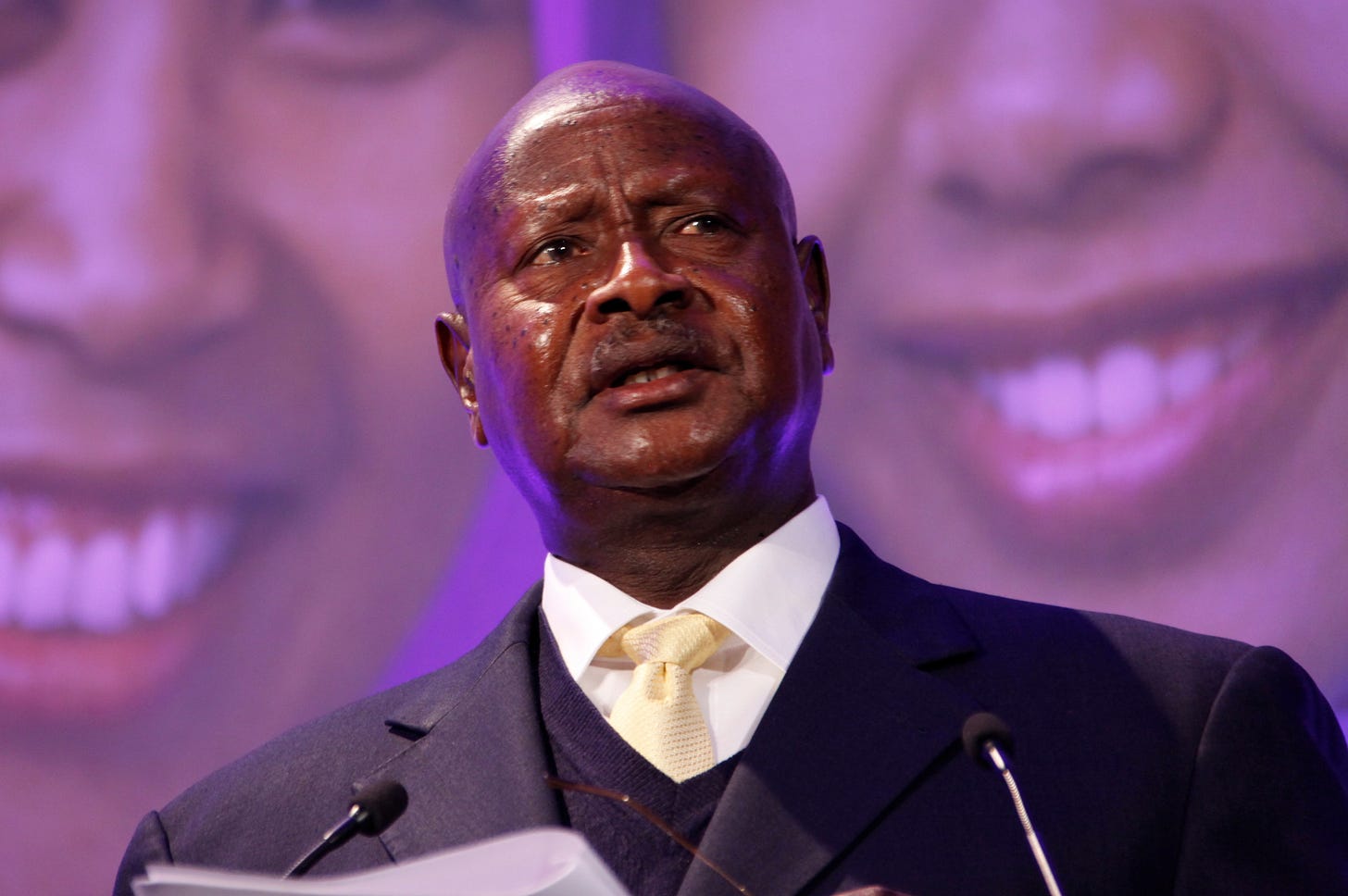

The Erosion of Legacy: Corruption in President Museveni's Government and Its Impact on Uganda’s Future

Restoring public trust must be a priority, necessitating a commitment to fighting corruption that extends beyond rhetoric.

In recent decades, the narrative surrounding Uganda has shifted dramatically. Once celebrated for its transformative leadership under President Yoweri Museveni since 1986, the country now faces a stark reality: the very ethos of development and democracy has been eroded by pervasive corruption. As global observers and Ugandans alike reflect on Museveni’s legacy, it becomes increasingly clear that corruption poses a paramount threat, undermining not only public trust but also the long-term prospects for progress and stability in Uganda.

A Promising Start: Museveni’s Early Years

When Yoweri Museveni ascended to the presidency in January 1986, he was greeted with optimism both domestically and internationally. His promises of economic reform, social justice, and anti-corruption measures resonated deeply with a populace weary from years of chaotic governance and civil strife. Initial reforms catalyzed economic growth, and Museveni was lauded as a transformative leader. His government’s focus on liberalization, privatization, and investment spurred significant economic advancements.

However, as the years wore on, this promising vision began to tarnish under the shadow of corruption. The institutions designed to combat graft became deeply infiltrated by the very practices they were meant to eradicate. The initial resolve to promote transparency and accountability waned as power consolidated around an elite few, often associated with Museveni’s inner circle.

The Nature of Corruption: A Culture of Impunity

Corruption in Uganda manifests in various forms: bribery, embezzlement, procurement fraud, and nepotism are rampant, with little recourse for those affected. The 2022 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index ranked Uganda poorly, highlighting the systemic nature of corruption, which thrives amidst weak institutional frameworks and a lack of political will to dismantle it.

Evidence indicates that many government officials engage in corrupt practices without fear of sanction. The public sector is perceived as one where graft is not only commonplace but expected, breeding an environment where ethical behavior is the exception rather than the rule. This pervasive culture of impunity erodes the very fabric of governance, leading to a profound disconnection between the government and its citizens.

Erosion of Public Trust

The ramifications of corruption extend beyond mere financial loss; they significantly impact public trust—an essential component of effective governance. In Uganda, steadily increasing disillusionment with government institutions has been reported, with many citizens believing that the system is rigged in favor of the elite. When individuals perceive that their leaders engage in corrupt practices without accountability, it breeds apathy and a general loss of faith in democratic institutions.

Surveys conducted in recent years illustrate this decline in trust. A considerable percentage of Ugandans now view their government as corrupt or ineffective. As public confidence wanes, political disengagement rises, especially amongst the educated class, exacerbating the already fragile relationship between the state and its citizens.

Economic Consequences: A Drain on Development

The economic implications of corruption in Uganda are profound and far-reaching. In general, research clearly shows that corrupt practices divert crucial public funds away from essential sectors, including education and health, thereby stunting overall development. The misallocation of resources translates into deteriorating health care systems, substandard educational facilities, and crumbling infrastructure—factors essential for fostering a thriving economy and improving quality of life for citizens.

For example, funds earmarked for rural infrastructure projects frequently vanish before reaching their intended destinations, leading to incomplete roads and bridges that hinder access to markets and services. This inefficiency and waste contribute to a cycle of poverty, making it increasingly difficult for Ugandans, particularly those in rural areas, to ascend from their current circumstances.

Moreover, the presence of corruption creates an uneven playing field for businesses. Potential investors often shy away from Uganda due to the perceived risks associated with corrupt practices, preferring to invest where the rule of law is more firmly upheld. This, in turn, constrains job creation and economic opportunities, fortifying a cycle of impoverishment.

Social Implications: Inequality and Unrest

The social implications of corruption in Uganda are equally alarming. As corrupt practices perpetuate inequality, a growing chasm emerges between the elite and the average citizen. Those within power are seen reaping the rewards of public funds while ordinary Ugandans grapple with economic realities marked by scarcity and uncertainty.

Additionally, the erosion of social cohesion fueled by corruption leads to disgruntlement among the populace. Citizens who experience or witness corruption often feel powerless and alienated, igniting feelings of frustration that can lead to social unrest. Numerous protests have emerged, driven by demands for accountability and transparency within government operations. However, such outcries are frequently met with harsh responses from security forces, silencing dissent and further aggravating public grievances.

Responses to Corruption: Promises versus Reality

In response to mounting pressure, Museveni’s government has introduced various anti-corruption initiatives, including the establishment of institutions such as the Inspectorate of Government and the Directorate for Ethics and Integrity. While these agencies were created to foster accountability, critics argue that they are often politicized, rendering them ineffective. Allegations of complicity among high-ranking officials challenge the legitimacy of these efforts, leading many to view them as mere window dressing rather than true avenues for reform.

Civil society organizations and media outlets have emerged as crucial players in the fight against corruption. Investigative journalism has uncovered numerous scandals, igniting public discourse and demanding accountability from government officials. Although these efforts face significant risks—such as intimidation and harassment—civil society remains a formidable force in raising awareness and pushing for systemic change.

The Role of International Actors

The international dimension of Uganda’s corruption crisis cannot be overlooked. Donor nations and international organizations often condition aid on good governance and anti-corruption measures. Yet, despite this pressure, the persistence of corruption raises questions about the effectiveness of these strategies. Critics argue that international actors must reassess their approaches to ensure that aid aligns with true governance reforms rather than mere compliance with superficial standards.

Moreover, there is a growing call for international sanctions tied to corrupt officials rather than entire nations. Such measures could force accountability and pressure those in power to reform. However, for these strategies to be effective, they require robust international cooperation and commitment.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The trajectory of President Yoweri Museveni’s legacy hangs in the balance, with corruption posing a significant threat to the very progress Uganda has achieved over the decades. To reverse the tide, a multifaceted approach is essential. Strong political will and genuine institutional reforms are needed to create a transparent and accountable government, while active participation from civil society can provide the necessary checks and balances.

Restoring public trust must be a priority, necessitating a commitment to fighting corruption that extends beyond rhetoric. Unless meaningful action is taken, Uganda risks entrenching a culture of impunity that not only jeopardizes its development but also threatens the stability and well-being of its citizens. The time for decisive action is now; without it, Museveni’s once-promising legacy may well devolve into a cautionary tale of what could have been.

Dr Peter Wandwasi obtained a PhD in Metaevaluation from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and he is a Research Associate at the Middle East and Africa Research Institute, Johannesburg, South Africa.