Individual And Societal Gains Realised After The Dissolution Of Communism In Central And Eastern Europe

The well recorded trajectory of Central and Eastern Europe since the fall of communism constitutes a powerful refutation of the notion that socialism offers any kind of sustainable path to prosperity.

Written By: Dr Brian Benfield

The political and economic transformation that swept across Central and Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980s constituted one of the most consequential shifts in modern history. The collapse of communist-socialist systems, long characterised by central planning, restricted civic freedoms, and structural economic stagnation, opened the way to democratic governance, free enterprise, property rights and market-based economies. Although the transition was initially turbulent and often socially painful, the long-run outcomes have been overwhelmingly positive. A substantial corpus of empirical evidence, ranging from public health and economic productivity to civil liberties and social welfare, records striking improvements over some three decades following the end of communist rule.

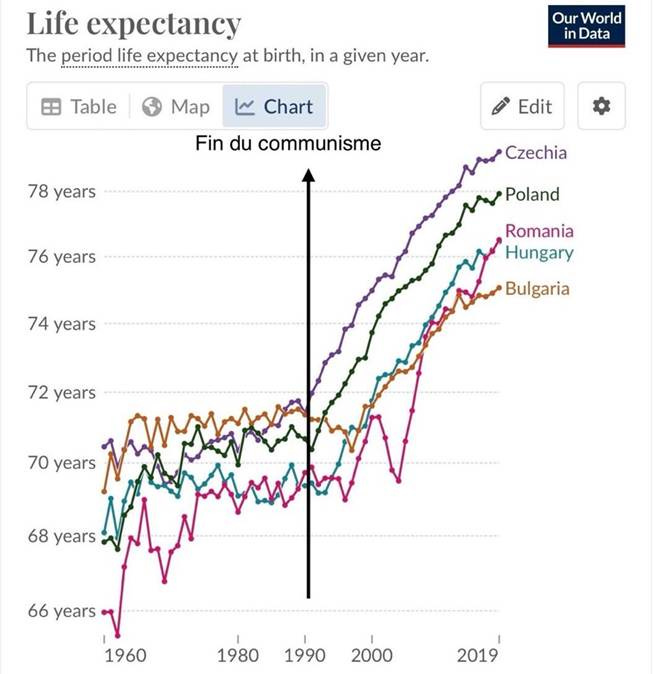

The steep rise in life expectancy illustrated in the accompanying graph is emblematic of a much broader and more comprehensive elevation in human welfare.

Indeed, one of the most compelling indicators of post-socialist progress is the dramatic improvement in public health and remarkable rise in life expectancy across the region. Under late period communist regimes, life expectancy had stagnated and even declined owing in part to a combination of poor-quality diets, limited access to modern pharmaceuticals, environmental degradation and underinvestment in medical infrastructure. In several states, rising alcohol consumption and high rates of smoking further eroded public health. These trends diverged sharply from Western Europe, where life expectancy continued to climb throughout the latter half of the twentieth century.

After 1990, however, the pattern reversed. Over the following three decades, countries such as Poland, Czechia, and Hungary recorded some of the fastest improvements in life expectancy in the OECD. Poland became a case study in rapid health-system transformation. Mortality from cardiovascular disease, the region’s dominant cause of premature death, declined precipitously following dietary liberalisation, the adoption of Western clinical protocols and the widespread availability of modern medications.

Environmental conditions improved as well. The closure or modernisation of heavily polluting industrial plants, combined with the adoption of EU environmental directives, reduced exposure to airborne toxins that had previously contributed to respiratory and cardiac diseases. The post-communist period also saw substantial improvements in food safety and nutrition, as price controls on agricultural inputs were removed and quality standards harmonised with those of Western Europe. The result was a healthier population, better medical outcomes and a sustained rise in longevity.

The transition from command economies to market systems ushered in a profound transformation of everyday life. Under socialist regimes, consumer goods were chronically scarce, often of poor quality and subject to pervasive rationing. Long queues, multi-year waiting periods for basic household appliances and the near-total absence of product variety were hallmarks of the socialist consumer experience.

By contrast, the post-communist era has produced an unprecedented expansion in consumer welfare. Real household consumption has risen sharply across Central Europe, with many countries effectively doubling or tripling living standards within a single generation. The liberalisation of trade and the entry of foreign retailers have brought a profusion of goods and services, from electronics and automobiles to clothing, pharmaceuticals and food. Housing quality too has improved as private ownership became the norm, mortgage finance expanded and renovation of run down, previously state-owned apartment blocks accelerated.

Crucially, the psychological dimension of greater consumer welfare, choice, convenience and access, expanded in parallel. For the first time in generations citizens enjoyed the ability to express themselves freely, to move freely, to purchase goods freely, to select among competing products and opportunities and to freely participate in the global economy, contributing significantly to the psychological and mental health of the nation.

The benefits of abandoning socialism therefore extended far beyond the consumer sphere. Although the early 1990s recession was severe, an inevitable consequence of dismantling centrally planned production structures, the medium- and long-term effects have been dramatically transformative.

Poland emerged as the region’s standout economic performer, avoiding recession during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and recording uninterrupted GDP growth for nearly three decades. Its GDP per capita, measured in purchasing-power terms, more than tripled from 1990 to 2020. Czechia, Slovakia, and the Baltic states likewise achieved impressive gains, converging with or surpassing the income levels of several Southern European countries.

A key driver of this expansion was foreign direct investment, which flowed into the region at unprecedented levels. Global firms established manufacturing bases in sectors ranging from automobiles and aerospace to electronics and pharmaceuticals. These investments modernised industrial capacity, introduced advanced technologies and integrated the region into European and global supply chains. The resulting productivity growth, long suppressed under central planning, became a key engine of economic development.

The political effects of the post-communist transition were no less significant. The end of one-party rule brought the restoration of civil liberties that had been severely curtailed under socialist governance. Freedom of speech, association and the press expanded rapidly, accompanied by competitive elections, multi-party systems and constitutional protections for individual rights.

While some states experienced episodes of democratic backsliding or institutional strain, the overall advance in civic freedoms since 1990 remains profound. Independent media, civil-society organisations, academic institutions and faith communities, all suppressed or tightly controlled under communist systems, flourished in the more open environment. Judicial systems were reformed and legal frameworks increasingly aligned with the standards of Western Europe, into which many post-socialist states successfully acceded.

Another signal achievement of the post-socialist era has been the restoration of personal mobility. Under communist regimes, travel abroad was tightly restricted and often heavily surveilled. The lifting of these controls unlocked an immense reservoir of human potential. Millions took advantage of open borders to study abroad, pursue careers in Western Europe, or engage in international commerce.

Labour mobility also produced powerful economic effects. Remittances from diaspora communities bolstered household incomes in countries like Romania, Bulgaria, Poland and the Baltic states. For individuals, the ability to seek opportunities globally represented a dramatic new expansion of life choices and possibilities.

The educational systems of Central and Eastern Europe also underwent significant renewal. Curricula that had been shaped by ideology were replaced by frameworks aligned with global academic norms. New institutions emerged and partnerships with Western universities multiplied. The accession of many former socialist states to the EU intensified these processes, granting access to research funding, academic networks and student exchange programs.

Moreover, the region experienced a cultural renaissance. The abolition of censorship permitted a flourishing of literature, cinema, journalism and public discourse. Minority cultures and religious communities regained visibility and the arts diversified beyond the narrow confines of socialist dogma.

The well recorded trajectory of Central and Eastern Europe since the fall of communism constitutes a powerful refutation of the notion that forms of socialism offer any kind of sustainable path to human welfare. Although the initial transition was naturally fraught with hardship, the long-term gains have been extensive and enduring. Longer and healthier lives, rising living standards, rapid economic growth, expanded freedoms, increased mobility and cultural renewal, collectively represent one of the most remarkable transformations of modern history.

The pronounced rise in life expectancy illustrated in the accompanying graph should not be viewed in isolation. It functions as a leading indicator of a far wider, historically significant enhancement in comprehensive human welfare that followed the transition back to individual liberty and a privately led economic order.

Dr Brian Benfield, retired professor, Department of Economics, University of the Witwatersrand, is a Senior Associate and Board member of the Free Market Foundation.