From social democracy to libertarianism: A journey through Bastiat’s vision of freedom

Bastiat’s principles offer a solid framework for a just and free society

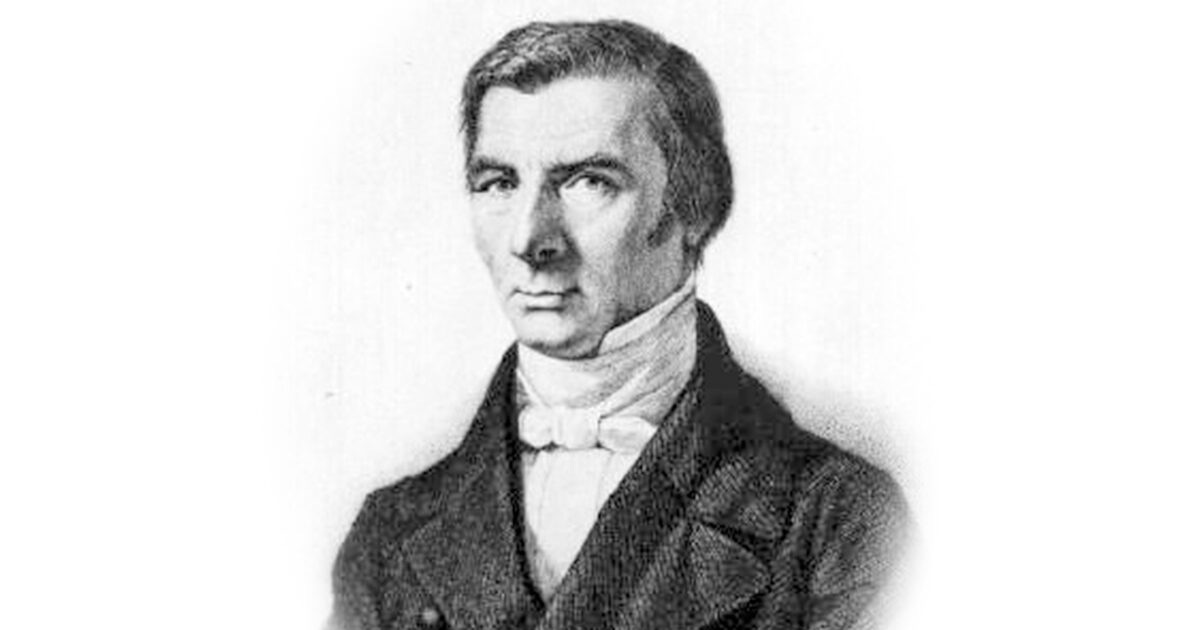

Not long ago, I was an avowed social democrat who believed that the state could balance both freedom and fairness. I was inspired by the Nordic model, where societies safeguard private property and encourage capital growth while redistributing wealth to ensure fairness. However, as I delved into legal philosophy, I encountered a copy of Frederic Bastiat’s magnum opus, The Law. This pivotal work not only catalysed my shift towards libertarianism, but also transformed my understanding of the law, rights, and the organisation of society.

Inherent rights and the role of the state

Bastiat’s first major insight emphasises that our rights – specifically, the rights to life, liberty, and property – are intrinsic and predate the establishment of any state. He argues that we acquire these rights through our efforts to subdue the environment and transform it into property using our mental faculties. This view marks a significant departure from traditional political thought, particularly that of a thinker like Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes arguably viewed the state as a paternal authority that grants and revokes rights as privileges. While his “sovereign” in the Leviathan is rooted in a social contract, its authority to grant and regulate rights positions it as a supreme arbiter of moral and legal order.

In contrast, Bastiat asserts that these rights are not the largesse of governance. The state lacks the authority to bestow or retract them, and it serves as a custodian rather than a benefactor. This understanding empowers citizens. If the state can author rights, it can also establish the rights of plunder.

The law as a custodian or tool of plunder?

Building on this foundation of inherent rights, Bastiat illustrates how citizens organise themselves to safeguard these individual freedoms through the establishment of law. This social contract embodies their collective right to self-defence. Individuals agree to form a government tasked solely with protecting those freedoms. Thus, the core duty of this government becomes clear: to uphold and enforce the law to maintain the liberties of individuals. When a state is founded on this principle, order prevails, and the result is a simple and just society. While no state perfectly embodies Bastiat’s ideals, Switzerland stands out for its strong commitment to individual rights, low taxes, and a limited government that fosters personal freedom and economic prosperity.

Bastiat further argues that this vision of a just society is upended when the law is diverted from its true purpose. It can become a tool of injustice that is wielded by the government to legitimise plunder. This corruption arises from humanity’s “fatal tendency” to profit from the labour of others. In South Africa’s case, the historical institution of slavery in the Cape Colony exemplifies this flaw. The legal framework there turned the law into a mechanism of injustice by enabling enslavers to exploit the labour of the enslaved for personal gain.

Legal plunder refers to exploitation that is sanctioned by law, while illegal plunder involves outright theft and coercion. Both forms persist in contemporary society and undermine justice. Governments often institutionalise rights of plunder by disguising state-enforced exploitation as fairness.

The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) exemplify this logic in their ideological program. Their advocacy for excessive taxation and redistributive policies effectively amounts to theft. By promoting the idea that the state should seize resources from individuals without consent, their proposals lay the ideological groundwork for converting plunder into a legitimate tool for achieving social equity.

Reflecting on my social democratic past, I contend that even in Nordic models, where capital growth and private property coexist, excessive taxation for equality undermines justice. The pursuit of fairness infringes on individuals’ property rights. This reveals a fundamental conflict between freedom and fairness. By heavily taxing capital to redistribute wealth, we take from individuals without consent. In doing so, we perpetuate the very injustices we seek to rectify.

In the South African context, a legacy of historical oppression and exclusion has contributed to significant socioeconomic disparities. Many argue that state intervention is necessary to level the playing field and address these inequalities. However, this view, as Bastiat reminds us, often conflates the government with society, leading to the misconception that rejecting state involvement means denying access to essential services. This is a crucial misunderstanding.

Take tertiary education as a case in point. The belief that only the state can provide access overlooks the potential of non-state driven solutions. Imagine South Africa as a society with minimal taxation – where citizens and businesses willingly contribute to public order and essential infrastructure. In such a system, taxation would not be theft; it would reflect a collective commitment under a social contract. While a significant portion of it would go towards infrastructure, the justice system, and defence, some of it could still be allocated to support education, albeit to a limited extent. Switzerland illustrates this point well by demonstrating that a robust education system can flourish in a context where taxation is low.

Alternatives to state-centric educational funding

Expanding on this solution, a significant portion of educational funding could come from public-private partnerships. The state could negotiate with private banks to secure loans for deserving students by offering affordable rates and reasonable repayment plans.

Furthermore, the private sector could play a key role in providing additional funding through philanthropic initiatives. Many companies across the globe voluntarily invest significant amounts into education and channel resources into scholarships and bursaries. This kind of commitment enhances access to learning and helps cultivate a culture of giving back. As a result, countless students are able pursue their educational dreams without the burden of financial constraints.

It must be acknowledged that concerns about student loans and the potential for debt trapping are valid. Nevertheless, this is where a free-market economy plays a critical role in creating mass employment, attracting investment, and lifting millions out of poverty. A thriving market not only addresses broader issues of access and opportunity but also provides the necessary environment for sustainable growth. In such an economy, students would have the means to repay their loans. South Africa lacks a truly free market approach to economics. This would contribute to a burden of debt should we have a comprehensive loan scheme for students pursuing education.

The consequences of rejecting the free market

The problem with rejecting free market economics in favour of a state-led approach to public policy is that it inevitably leads to plunder. Redistributive policies aimed at achieving equality and access always rely on excessive taxation and the coercive transfer of wealth. Over the past thirty years, the African National Congress (ANC) has illustrated this trend by implementing repressive policies like Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE), which confiscate the wealth of businesses to reallocate it to others. Unfortunately, these measures have not delivered the desired outcomes, and they have left many in the same cycle of poverty while enriching a select few.

The role and responsibility of businesses

Having examined the detrimental effects of state policies on wealth distribution, it is necessary to address the fallacy that businesses bear a social obligation to pay excessive taxes as a means of rectifying these inequalities. The core issue with this reasoning is that it suggests businesses’ profits are a collective good simply because they operate within society. This is not true.

The profits of businesses rightfully belong to them because they are earned by providing value and engaging in voluntary exchanges with consumers. Businesses do not coerce anyone into buying from them. They offer goods and services that individuals choose to purchase based on their own preferences and needs. Moreover, businesses fairly compensate employees who contribute value to their operations.

When businesses cause harm to others, they can be held accountable through legal recourse without the need for extensive government regulations that infringe on individual liberties.

The only legitimate case for taxation concerning businesses is limited to maintaining public order and infrastructure. Such taxes are important because they operate with their consent, which acknowledges their role in supporting the society in which they thrive. Excessive taxation aimed at redistributive policies is problematic because it is a form of theft.

Businesses already contribute their “fair share” to society by meeting consumer demands and providing essential goods and services. They invest significant resources annually into philanthropy and charitable initiatives, which demonstrates a commitment to social responsibility without state coercion. This voluntary action underscores that there is no need for the government to impose additional burdens on businesses.

Towards a free society

In contemplating the blueprint for an ideal society, it becomes clear that a framework resembling Bastiat’s vision offers a pathway to genuine freedom. This vision entails a society supported by a limited government that serves to protect rights and a free-market economy that fosters accessibility and opportunity for all.

Any vision diverging from this ideal fails to offer a genuine path to freedom. As the late Milton Friedman aptly noted, a society prioritising equality over freedom risks obtaining neither. The EFF endorses legalised plunder by luring supporters with promises of redistribution funded by the wealth of other individuals. This cycle depends on continual looting to sustain welfare commitments, and it also reinforces patterns of dependency and exploitation.

I wholeheartedly affirm that Bastiat’s principles offer a solid framework for a just and free society. His insights illuminate the inherent conflict between freedom and conventional ideas of fairness and underscore the need to build a society that prioritises the former.

Ayanda Sakhile Zulu holds a BSocSci in Political Studies from the University of Pretoria and is an intern at the Free Market Foundation.

Another Ayanda S Zulu banger. Your articles are a delight